|

|

|

http://www.varalaaru.com A Monthly Web Magazine for South Asian History [187 Issues] [1839 Articles] |

|

|

|

http://www.varalaaru.com A Monthly Web Magazine for South Asian History [187 Issues] [1839 Articles] |

|

Issue No. 29

இதழ் 29 [ நவம்பர் 16 - டிசம்பர் 15, 2006 ] ஓவியர் சில்பி சிறப்பிதழ் ]

இந்த இதழில்.. In this Issue..

|

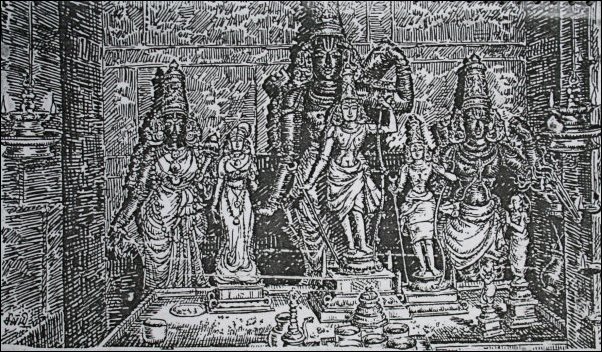

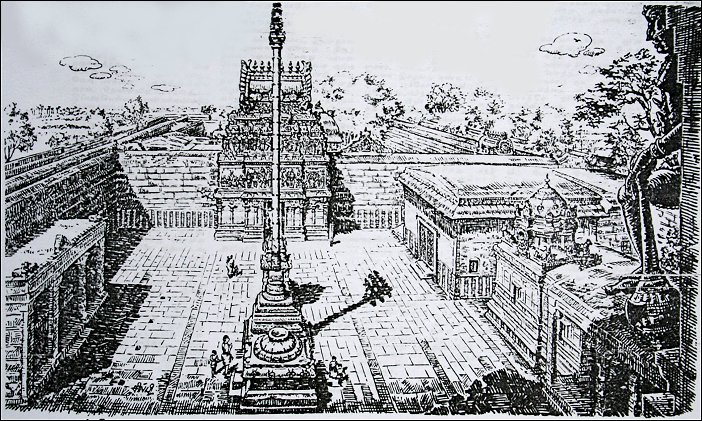

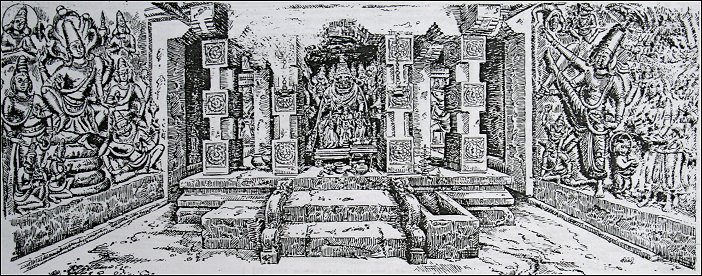

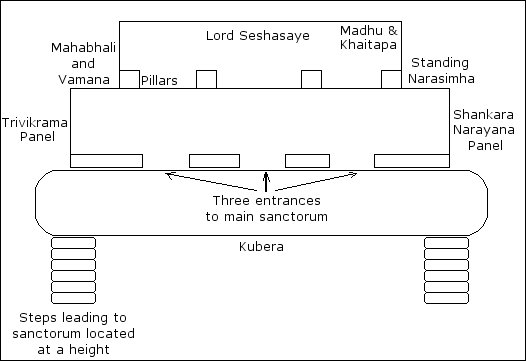

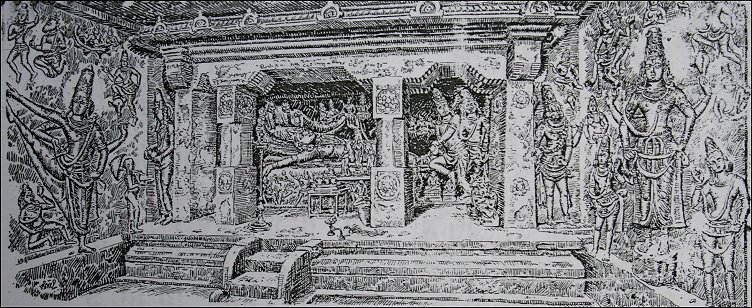

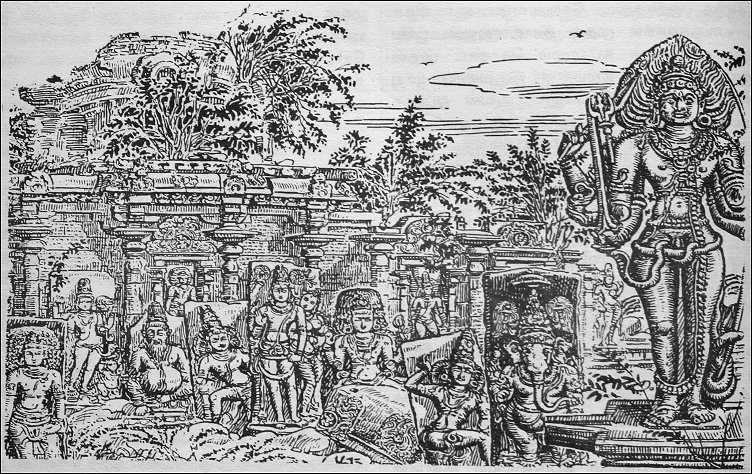

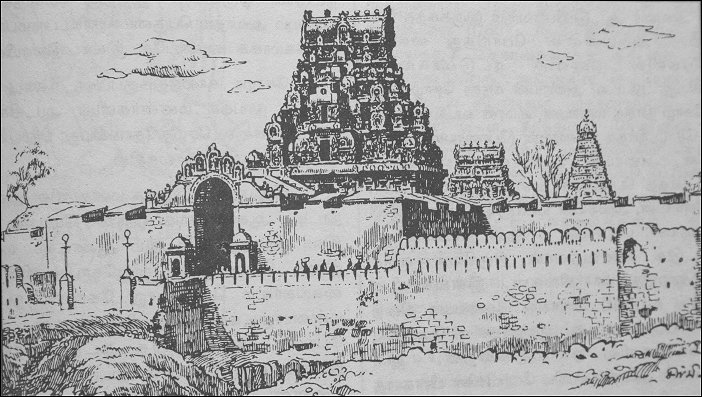

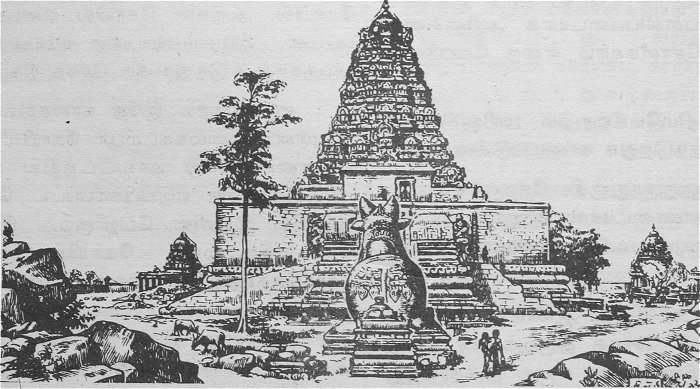

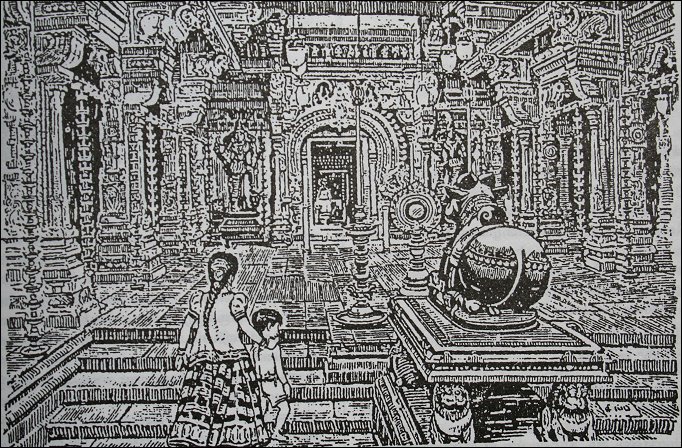

The purpose of this article is to explore and highlight chosen line drawings of Late Artist Sri Silpi and thereby attempting to highlight some salient features and characteristics that would enable us to appreciate his impressions better. Silpi was best known for his line drawings though he had also done numerous colour paintings in oil. Most of his colour impressions captured the main deity in the sanctum sanctorum – often accompanied by the processional Hindu deities and other metallic images in bronze. The purpose of these colour drawings were simple and straight forward: they were meant to be framed and worshipped in the Tamil Hindu households. 40 to 50 years ago, photography was totally prohibited in the sanctum sanctorum of almost all temples in Tamilnadu. Hence the only medium to record the deities of the sanctum sanctorum was colour drawings. Though many other artists have undertaking this task, Silpi excelled in this undertaking by recordings the deities – in all their originality and grandeur. He did not let his creativity hamper the process of recording the deities as they were seen and felt. The best example I can quote is the way Slipi has recorded the well known deity of Thirupathi – Sri Venkateswara Swami. Due to the way the deity is adorned with jewels and a big crown, to a viewer, the head of the deity appears to be a bit bigger than the normal proportion expected. Though many other artists have rendered their versions of Sri Venkateswara, nobody – not even the official artists who rendered the drawing that is available from Thirumala Thirupathi Devastanam – has recorded this detail. I was totally surprised when this was captured in Silpi’s rendering. This is just one simple example. Interested viewers will be able to spot many a detail if they will analyze Silpi’s paintings properly. Since this article is about Silpi’s line drawings and not colour impressions, let us bestow our attention to some characteristic features of line drawings and how Silpi capitalized his divine talents in this direction. *********************************************************************************************** Light plays a major role in our lives. It illuminates our world. When the nature of light changes as the day passes through the night, so does our visualization of the world around us. Light has an effect not only on the external world but also on the internal private world of ours. The feelings and ambience of a medium light feels different than the one in bright day light and so on. To artists and photographers, light is an important medium to consider. An artist uses light to produce the level of atmosphere he wishes to portray in his paintings or photographs. The direction from which light is coming, multiple sources of light that illuminate the scene, the power and intensity of each light source, whether it is artificial light or natural sunlight, indoors and outdoors – all affect the artist’s impression. With this background in mind, let us view two classic line drawings of Silpi and try to understand how he has applied the concept of light. The first is the rendering of Sanctum sanctorum of Sri Rama Temple in Thiruvallur (near Chennai), Tamilnadu. (Painting courtesy: Dinamani Kadhir)  The mūlabhera and utsavabhera images of Sri Rāma temple, Thiruvallūr Painting one: The Mūlabhera and Utsavabhera Images of Sri Rama, Lakshmana, Seetha and Hanuman at the Sanctum Sanctorum of Sri Rama Sannidhi, Sri Veeraraghava Swami Temple Complex, Thiruvallur (Evvullur of Divya prabhantham fame) The sanctum sanctorum of Hindu temples are usually without any corridors and the main deities (called Mulabheras) and processional deities (called Utsavabheras) are to be seen with the help of natural oil lamps lit and the light lit by the temple priest as a part of worship. Devotees are supposed to view the gods only in limited light. Silpi captures this overall ambience of a dark room with limited lights by almost filling the entire painting with lines. Especially note the crisscross lines on the sanctorum wall. The granite slabs that have been used to construct the walls as well as their alignment are also recorded. In order to give the perspective to the viewer, it has become necessary for Silpi to make the side walls look darker than the back wall. The major sources of light in the sanctorum are the two main oil lamps, available both on the right and the left. Additionally, smaller oil lamps are available on the right (of the viewer). The lamp on the right is closer to the deities than the one on the left. The net effect of all this is that the light cast from the right of the viewer is stronger on deities than the left. Silpi records this effect by giving a very dark shadow behind each Mulabhera image. It also helps to give a sense of projection and the concept of space between the images and the back wall. The main deities in South Indian Hindu temples are generally made out of granite or a mortar (traditionally called as Sudhai) though wood is also a permitted material (1). Irrespective of this constitution, all images look very black and dark. This is because special oil is anointed on top of the images almost at regular intervals. Because of oil, the surface of the Mulabhera images seem to reflect some light and this is recorded in the present masterpiece by means of white space in between curvy lines. This is one of the characteristic features of Silpi’s art works. Later, we will see how this master artist clearly changes his technique when it comes to bronze images. (1) The Mulabhera image of Sri Vishnu Temple (Ulagalanthan) of Thirukkovilur is in wood until today. The famed Atthigiri Varadhar Image of Kanchipuram Varadharaja temple is another example of wooden images still in existancea The Utsavabhera images are recorded with less complexity in front of the Mulabheras. Small pieces of flowers and possibly thulasi (the sacred leaf) are shown sprinkled on the platform in which Utsavabheras are shown. Obviously it is the result of some of the poojas performed to the deities throughout the day. All equipments and vessels used during pooja like the bell, Chadari and Panchapathirams (Five sacred vessels) have all been captured to the fullest possible detail. The example which we discussed till now is a good example for Silpi’s expertise in indoor art. Now, let us consider another example to highlight the artist’s mastery over outdoor light and shade effects as well as the concept of perspective. *********************************************************************************************** Perspective is a fundamental concept in art and photography. It is this feature that helps an artist to capture and represent the effect of distance in art. To the human eyes, things that are closer to them appear in their actual proportions whereas when the same things are kept at a distance they appear smaller. This is why walls – though they are of same height throughout – appear to taper in at the end. The capability to represent this effect of perspective is a fundamental requirement in art. Silpi not only mastered this art of perspective but undertook to draw difficult positions and situations that would challenge him. Any novice learner of art would realize that it is easy to represent or capture the effect of perspective from ground; because the human mind is always used to see objects from standing on the ground. But things become difficult when we were to stand atop at a height and represent things that are beneath the feet level. Here the perspective becomes a different game and most likely a difficult game too. With this background in mind, let us view Silpi’s portrayal of the inner corridors of the famous Shiva temple at Thiruvālangādu – near Chennai, Tamilnādu.  Inner corridors of the famous Shiva temple at Thiruvālangādu Silpi always had the habit of giving viewers a good view of the entire temple complex and when one drawing was insufficient, he did not hesitate to render different views of the temple complex that covered all the positions and impressions the ancient temple bestowed upon him. This is clearly visible whenever he did the art works for a series on temples of Tamilnādu. Coming back to the painting under discussion, the very first detail to be noticed is the position he has taken while representing this portion of the temple. It seems Silpi had sat down on the first tier of the front Gopura (Temple tower) while rendering this line drawing. This is well attested by the Dwāra Palaka (Door guardian) he represents on the right hand side of the viewer. Usually, door guardians are found on either side of the central recesses in all temple towers. Silpi seems to have sat in the first tier and viewed the temple complex via the recess. On the side he sat, one of the Dwāra palaka’s legs and portion of the body are visible – the other one obviously beyond the portions of the temple he wished to capture. By recording this guardian deity, Silpi creates the impression of height in the drawing. The dark colour of the palaka is because of the lengthy shadow falling upon him – a concept that will applied throughout the painting. Having given the notion of height, naturally, the purpose now is to represent what is seen beneath. The very first entity is the Dwajastambha (or the temple flag post) which is another marked feature of all south Indian temples. The temple flag post starts from the ground but it rises well above the height in which Silpi is seated. This is captured by a tight representation of the top portion of the post which is shown to be above the viewers head – in terms of its perspective. Rest of the buildings is of smaller height and hence only their top portions are visible. One can notice slight bends on all top surfaces on the right hand side buildings – these are slants provided for rain water to seep out. The inner gopura and other portions of the temple are represented one behind the other. While the concept of height was emphasized by means of a side dwārapalaka, the concept of the plain surface over which all the different buildings of the temple raise is well captured by means of shadows. A strong source of light seems to have been emanating from the left horizon – slightly behind the viewer. If we were to apply the concept that most temples face east (and assuming the present temple under discussion also faces east), it will be clear that the drawing was done along the morning hours when sun rises from the east horizon. All objects are casting their respective shadows on the ground in which they are installed. Especially look at the precision with which the shadow of the top portion of the temple post has been captured. While this top portion was not visible from the position in which viewer is seated, the shadow gives a good idea of its constitution. Devotees can be seen near the flag post. This is to give the viewers an idea of the overall dimensions of the temple. By giving a base human reference, the mind automatically compares the height of the flag post with that of the human and understands the sense of proportion better. While all trees are shown with meager lines, the one on the extreme right is in silhouette form. This is because of the shadow of the big temple tower (in which artist is seated) falling upon the same. *********************************************************************************************** The next drawing we are going to discuss illustrates the concept of space and the artist’s ability to view or manipulate space right in front of him. The cave temples in Namakkal, near Selam in Tamilnadu are an extraordinary representation of master craftsmanship achieved during the days of pallavas monarches in the north & the pandiyas in the south. There are two cave temples located on the rocky mountain that rises right at the centre of this small town. The Narasimha Vishnu Gruha (or the Vishnu temple built for Lord Narasimhā – one of the ten incarnations of Lord Vishnu) is located on the cave in ground floor while the Seshasayē temple (or the temple of Lord Vishnu inclined on the snake ādisesha) is located in a cave at the middle of the mountain. Late brāhimi script inscriptions of the transition period are available near the Seshasayē temple and the cave itself might predate the sculptures of the cave temple. The temple complexes are believed to have been built by the Satyaputho adiyaman kings of the region. One of the inscriptions call the temple “Adhiyēndra Vishnu Gruha” or the Vishnu temple of Adhiyēndra. Th Narasimha temple consists of a fairly large sanctum sanctorum with complicated relief sculptures rendered on either side of the sanctorum walls. Considering the fact that no mistakes can be committed in such cave temple projects, it is with awe that we are to wonder the complicated structural groups with a number of icons and sub-deities that the artist has skillfully captured. Let us come back to Silpi’s line drawings representing the various sculptural panels of Namakkal. In my humble opinion, the Namakkal icons represent one of the very best of Silpi’s line drawings. Partly this could be due to the fact that this was his native birthplace – Silpi hails from Namakkal. With numerous drawings, he captured all the artistic essence left behind by the sculptures of Adhiyēndra and easily transport us to a bygone era of cave temple building. The first drawing we shall see is the portrayal of Sanctum sanctorum of Narasimha temple. Here, as we shall realize soon, Silpi’s idea is just to provide viewers with an overview of how the sanctorum looks like, where the sculptures are located etc and wet them with the atmosphere.  Silpi captures the atmosphere of Narasimha cave temple at Nāmakkal I’ve been blessed enough to visit this shrine several times and words are falling short as I try to explain the skill and verve with which Silpi has captured the atmosphere in this first drawing. This cave temple is a pretty short one and is not as lengthy as it seems to appear in the drawing. The walls on either side of the main mūlabhera sculpture are straight walls projecting from the rear end. Both have panel sculptures facing one another and there are panels on the rear wall as well. Silpi slightly expands the narrow sanctum in its width so that there is enough space for him to represent all that captures his eye. This is something which a photographer might not have been able to do. Herein lies the genius of the artist in Silpi. Silpi represents the details of two panel sculptures on the side walls on either side of the drawing – to the detail possible. Both are extremely important panels from an iconographic standpoint. Especially the one on the left hand side of the viewer representing Vaikūnda Narayana is not available anywhere else in Tamilnādu. Flanked by Shiva and Brahma as well as Chandra and Surya, Narayana sits in his favorite Snake – while the Narasimha himself is in the praising position on the bottom portion of the panel (below Brahma). The panel on the right side is the famous Trivikrama episode of Srimad Bhagavatham. On the right side of the panel, child Vāmana is requesting king Mahābhali for 3 feet of land. And on the right he takes his Viswarūpa or the giant posture measuring sky and earth with his two feet and asking where to ask for his third feet. The main deity Narasimha is represented in the back wall with limited details. The rough surface of the rock boulder is well bought out in the steps leading to the main deity. The relatively simple adhistana (temple basement) of early times, the square – 8 faced pattai – and then another square shaped pillars and the podhigais with tharangam – all remind us of the pallava cave temples of Thondai mandalam. Two more panals are located on the extreme rear. Only very little portions of these panels are visible from the position we are in. Though not fully visible as yet, the Varāha panel of the right side already starts capturing our attention. In a way these two panels seem to have enjoyed greater attention of Silpi and he has rendered two dedicated line drawings to capture them. The proportions with which these have been captured are beyond what I can express here and viewers can enjoy them fully by visiting the cave temples in person.  Varāha mūrthy - Original sculpture and Silpi’s drawing While the Narasimha temple is a feast for the eyes and soul, the Seshasayē cave temple astounds us by the its icons of magnificent size and proportions. The Seshasayē of Mamallapuram is a class of its own, no doubt – but the Namakkal sculpture exhibits certain traits which makes it an unparalleled sculpture in the artistic history of Tamilnādu. It is also the only Seshasayē sculpture of that period in which all the accompanying deities (upadevatās) can be clearly identified with certainty: for each of them carry an inscription below them. The major sculpture of the reclining Vishnu is flanked by the asurās (daemons) Madhu / Khaitaba as well as a number of deities who are seen behind the lord. The walls on either side of the main deity are adorned with various sculptures. Once again, a personal visit to this cave temple is called for – in order to fully appreciate Silpi’s portrayal of this temple. I shall try to explain as much as I can, but I would strongly recommend a visit to the temple. There are three entrances to this cave temple. This is not very unique to certain other temples of reclining Vishnu: Sri Padhmanābha temple at Trivandrum as well as at Thiruvalla has three entrances to view the face, hip and feet of the lord. The position Silpi has shown in his art is something that does not exist in reality in the Namakkal temple. The layout is somewhat like the plan I have provided below.  Layout of Sēshasayē temple in Namakkal Whatever may be the entrance through which one enters, there is very little space between the doors and the platform. On the platform, the arthamandapa quickly ends and the garbagruha starts thereafter immediately. And unless the viewer turns to his left or right, it is not possible to see the sculptures on either side of the walls. Silpi takes a position which will enable him to represent the main deity as well as the ones on the flanking walls. He might have thought that if these were represented as individual sculptures in different drawings, then the whole idea of sculpting so many things in small space available might be lost in the mind of the viewer. Thus, he takes extra precautions and tries to represent the different perspectives – even at the cost of losing the basic geometry of the cave to some extent.  Silpi’s portrayal of Sēshasayē (Aranganatha) cave temple sanctorum The sculpture on the right hand side of the viewer is one of the most important and one of the earliest Shankara – Nārayana representations in Tamilnādu. Though Pillaiyarpatti could be an earlier icon, the size chosen for the panel, flanking deities, ornamentation and overall proportions make it stand apart. *********************************************************************************************** Silpi’s art works carry certain sense of historicity in them. There cannot be a better example for this statement than the Thiruvalanchuzhi Kshetrabāladēvar temple. Silpi’s art fittingly captures the pathetic state in which the temple was – 50 years ago. This temple as well as the entire temple complex of Thiruvalanchuzhi is unique in many respects. The Kshetrabāla devar sub-temple is the first dedicated temple to the deity in Tamilnādu. Earlier, only Bhairavā was established as one of the eight parivāradevatas (sub-deity) in many Shiva temples. The temple was built by the royal queen of chola emperor Rajaraja-I, Danthisakthivitanki alias Lokhamādevi. The temple complex of Valanchuzhi vānar is massive and houses Swētha vinayagar shrine (called Vellai Pillaiyar in late chola inscriptions) as well as the first known dedicated temple for Kāli, in the name of ēkavēri. All these special features did not help the temple’s destruction and as we see the status of affairs fittingly captured by the master artist, one finds it difficult to control his or her emotions.  The crumbled Kshetrabāladēva temple at Thiruvalanchuzhi As it can be seen, the entire temple complex seems to have given way to serious destruction and the mūlabhera image – Thiruvalanchuzhi Kshetrabāla devar – seems to have been standing alone in the hot sun and heavy rains for several years. Later on, this icon was moved to Rājarajan Manimandapam (Memorial hall for King Rājaraja). An extraordinary piece of sculpture in its dimensions and execution, the Kshetrabāla devar seems to have enjoyed the royal patronage of many kings since Rajaraja-I’s queen Lokhamadevi established the shrine. The Ganapathy statue that is lying next to Kshetrabāladēvar has been rated as one of the very best portrayals of the god in the hands of chola sculptors. The Dwārapalaka, Dakshināmurthi, Uma sakitha – all seems to have been lying in the ground, totally uncared for. The situation did not improve as late as 2005 and www.varalaaru.com wrote several articles and editorials about the importance of this temple. Now, thanks to the efforts of temple authorities and philanthropic individuals like Mr.Sundar Bharatwaj, the entire temple complex has undergone massive renovations. Considering the importance of epigraphs, sculptures and architecture of the temple, Dr.M.Rajamanickanar Institute of Historic Research has conducted a survey and analysis of the temple – the details of which are available in the book “Valanchuzhi vaanar”. We need to visit the temple complex and compare Silpi’s drawings with what we see – in order to understand the quality of renovations. Another excellent example of the element of historicity in Silpi’s drawings is available in his portrayal of Rājarājēswaram (or the Brahadēswara temple) at Thanjāvore. The first drawing shows the front view of the temple. It is interesting to note that the temple complex had trees in the past. Another detail to notice is the structure of the moat and the fort walls.  The Rājarājēswaram temple (Front view) – as captured by Silpi The second drawing presents a very unique perspective of the temple Srivimāna – not captured by any other photographer or artist.  A different view of Rājarājēswaram temple Srivimāna In this drawing, Silpi seems to be sitting in front of a Hanuman statue – obviously a very late sculpture, which seems to have been housed near the temple complex. The branches of the nearby tree are extending their hands with free will and ease. These have been cleared by the Archaeological survey of India which is maintaining the monument. The only surviving evidence for their presence is the late artist’s work. It will be interesting for the students of history to note that it did not discourage people to start local hanuman worship, right next to the massive temple complex. Or whether it was meant to be a fort guardian deity, we do not know. Yet another example of Silpi’s drawing capturing the status of affairs several decades ago, is available in his Gangai Konda cholapuram temple drawing.  Gangai konda cholapuram temple – Front view *********************************************************************************************** I can go on and on like this and probably try to capture very little or none of the essence of Silpi’s art – but I have to stop somewhere. As I try to explain and explore, I clearly realize the limitations of words when it comes to appreciation of art. For example, what do you think can be written about this extradinary portrayal of mukha mandapa ?  Every detail – captured to the finest precision The best way to remember and honor Silpi is not only by keeping his representations of the divinities in the pūja room but in taking time to appreciate the life and verve in his art works. The very best way I would recommend to do this, is to take his drawings to the actual venue wherein he sat and drew and compare the real scene with what is depicted. Silpi’s art works are sources of a number of researches and I fervently hope that at least few students of art will explore the magic art of Sri Silpi and the divine spirit in him that guided and kept him going along the un-trodden path. this is txt file� |

சிறப்பிதழ்கள் Special Issues

புகைப்படத் தொகுப்பு Photo Gallery

|

| (C) 2004, varalaaru.com. All articles are copyrighted to respective authors. Unauthorized reproduction of any article, image or audio/video contents published here, without the prior approval of the authors or varalaaru.com are strictly prohibited. | ||